Needs Improvement

There was always someone in class who, despite being odd, escaped bullying and even achieved adulation by illuminating the mundanity of school in his own unique way. At Wormwood Elementary, Homeroom 1E, this someone was Yann Mehta-Zablonsky, famous for his mazes.

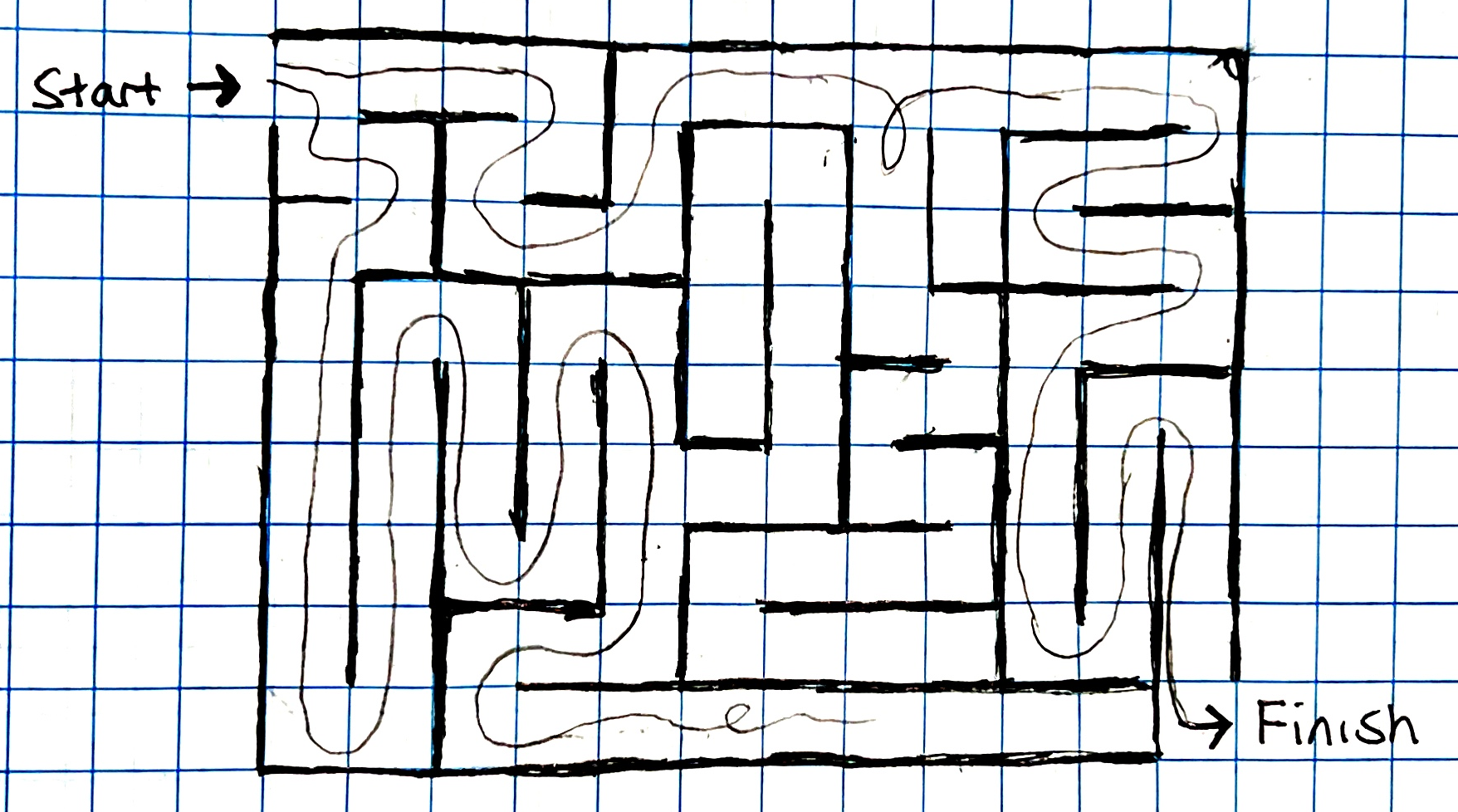

It all started with graph paper, a No. 2 pencil, and a Health class so dreary it extended its length, like how humidity intensifies heat. In a moment of inspiration borne from sheer boredom, Yann, instead of taking notes for that day’s lesson on the brain, decided to make a maze. It came out like this:

Yann would be the first to admit that this was not a very good maze, being predictable, incompact, and, worst of all, solvable by the right-hand-rule. But still we see in this very first maze some of the signature features present in nearly all of Yann’s mazes, perhaps most markedly the fake, almost sarcastic path to the finish line in the bottom-right corner. In this scan it is seen solved by Yann’s crush Sarah, who saw the neatly folded and discretely passed maze as a fun diversion, not the abstracted love letter it might have been in Yann’s head.

Another student must have spotted Sarah solving the maze and instantly become envious of the opportunity for distraction, especially during Mrs. Dion’s digressions on dementia, a far cry from last week’s viewing of Supersize Me (Educator’s Edition). Through Sarah he traced the source of this invention, and promptly asked Yann for a maze of his own. Even though it wasn’t a boy Yann particularly liked, the exchange of a small puzzle for peace at recess, gym class and lunch was a more than favorable deal.

Yann’s puzzles quickly found their way into the hands of all of 1E’s fifth graders. They grew in quantity, quality, complexity, and size, with his mazes regularly filling the letter-size page. It wasn’t long before other outsiders tried to follow Yann’s path into the in-group, spawning several other maze makers. This became a problem for Ms. Arthur, who noticed the blatant misuse of her stack of graph paper, meant for math problems. “This needs to stop right now-” she said with that special shrillness of young female schoolteachers, “I’m not the graph paper supplier of the world.” But Yann turned himself in before Ms. Arthur began her full-scale investigation, knowing he was a favorite, and would be forgiven. Her anger even turned to sympathy with poor Yann upset at the plagiarism of his one and only claim to fame, and though Ms. Arthur reminded Yann that ‘imitation is the most sincere form of flattery’, it did little to placate him, emotional maturity not something eleven-year-olds, especially neurodivergent ones, are known for.

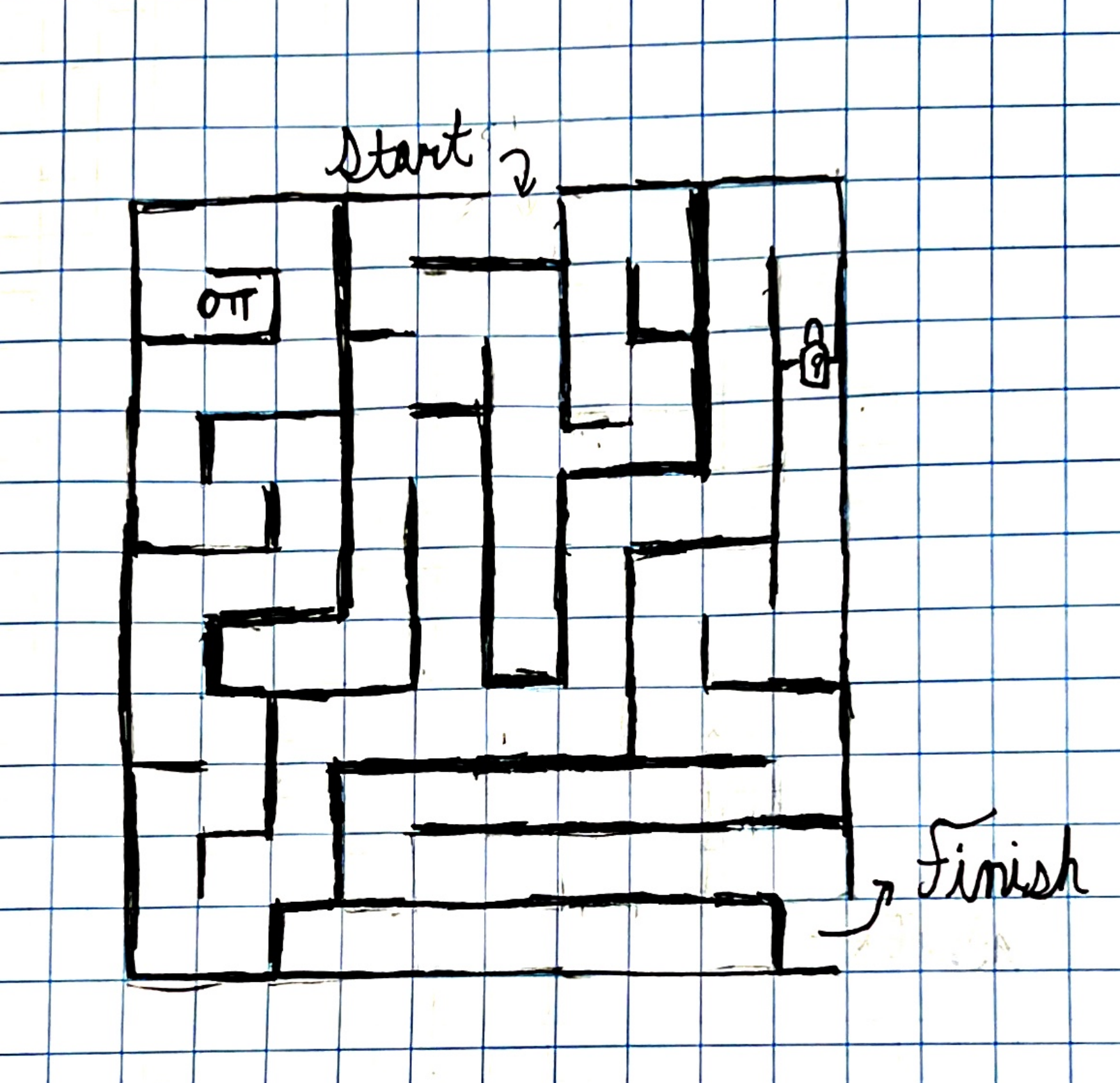

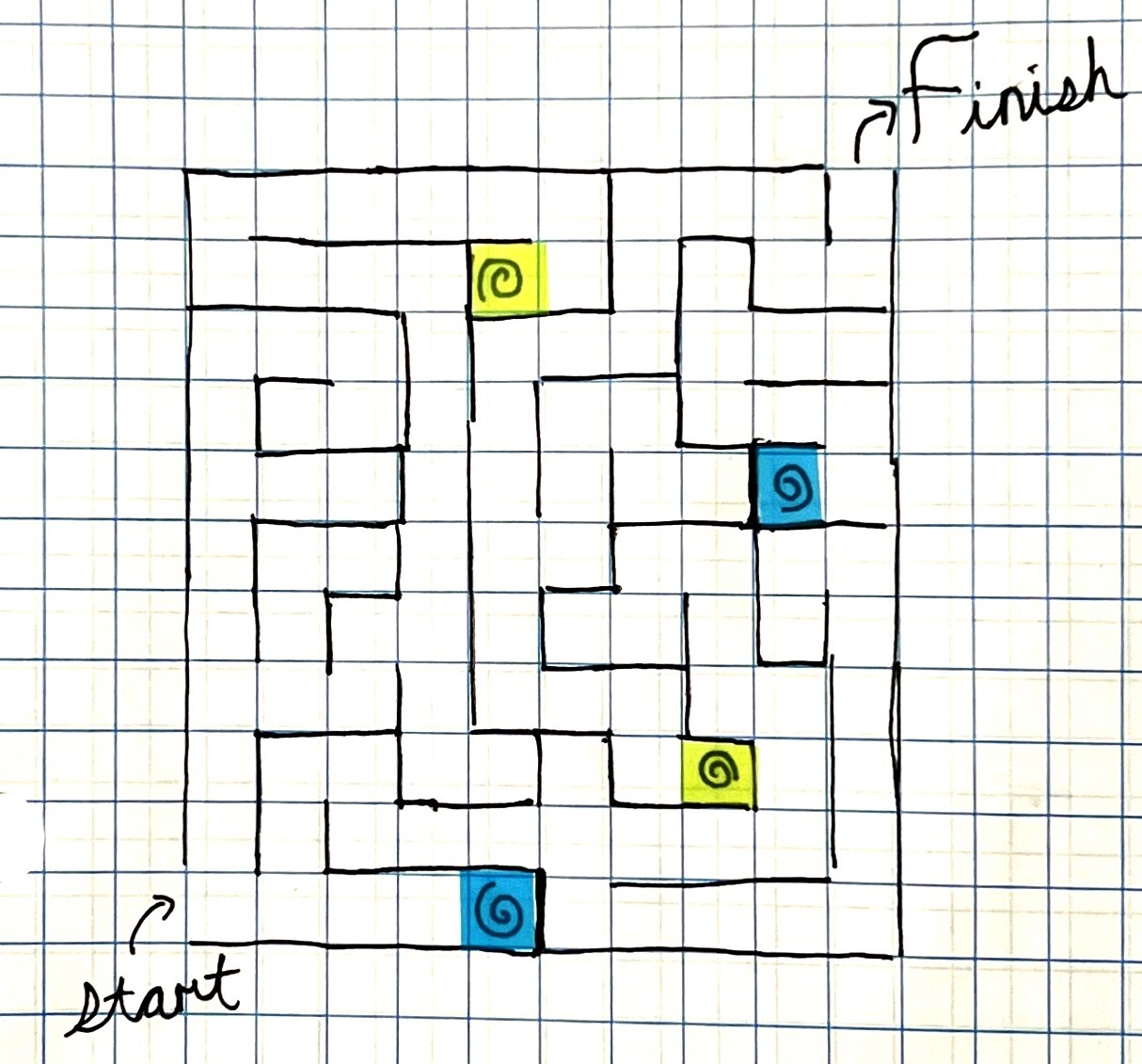

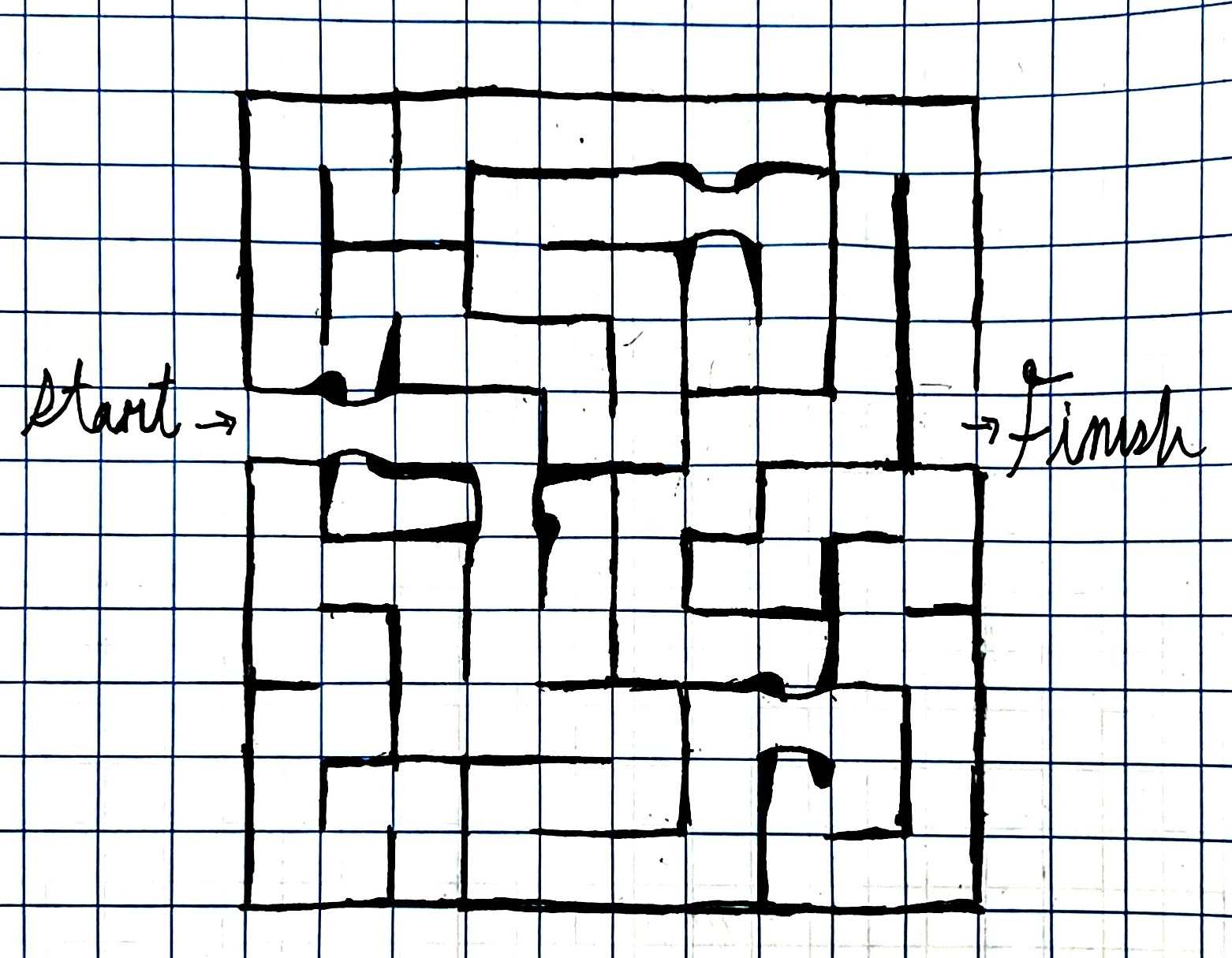

So without the legal structures necessary to patent his mazes (he was in fourth grade), Yann instead decided to take them to the next level. Here are my lazy (though atomic) demonstrations of the ideas introduced in what I term his ‘experimental period’:

Keys

Portals

Tunnels & Bridges

His imitators (myself one of them) could hardly keep up with the rate of innovation. By the time we had discovered, analyzed, and learned to replicate each new feature, Yann had not only introduced a new one but also seamlessly integrated it with all the others. The bar had been raised to a level we questioned the worth of even trying to reach. Most of us gave up. Yann won.

But the mazes, like art, had become an end in themselves, and Yann was already thinking about his next step, his boldest evolution: breaking from the grid. Already a master craftsman of mazes on graph paper, the void of the blank page was the only worthy challenge. Sadly there are no surviving works from his organic period (no finished ones, anyways), evidence of his difficulties. I suppose Yann was always frustrated by the lack of a unified aesthetic, or unsatisfied with curves that even suggested right angles (holdovers from the days of blue squares), or unsure, even, of their worth as puzzles. Here’s a draft I found crumpled in the garbage can of 1E:

Would he have eventually finished such a maze? Would that have been his magnum opus? Would he have allowed anyone to solve it with anything but a finger? And then how would he top that? We will never know, as Yann’s career was halted by a quarterly evaluation from Mrs. Lee. Despite his A- in English, Yann was nevertheless given a “Needs Improvement” in both Behavior and Concentration. Plus, Yann was taking all her printer paper. It was the catalyst for a visit to the school psychologist, who subjected Yann to a one-hour computerized test in which he had to type “A” for a flashing red square, “S” for a flashing yellow square, and “D” for a flashing blue square. His score wasn’t very good.

After a long hiatus, Yann received a commission from none other than Sarah, the original muse. And though her name was printed in Yann’s handwriting, congruent with the customary ‘Start’ and ‘Finish’, she was no doubt a little disappointed with what she received (I definitely was, when she showed it to me). This, his final work, can only be seen as a statement piece, being, well, open to interpretation:

Austin, Texas. November 2022